Many organizations struggle with the all-time increase in IP address allocation and the accompanying need for segmentation. In the past, governing the segments within the organization means keeping close control over the service deployments, firewall rules, etc.

Lately, the idea of micro-segmentation, supported through software-defined networking solutions, seems to defy the need for a segmentation governance. However, I think that that is a very short-sighted sales proposition. Even with micro-segmentation, or even pure point-to-point / peer2peer communication flow control, you'll still be needing a high level overview of the services within your scope.

In this blog post, I'll give some insights in how we are approaching this in the company I work for. In short, it starts with requirements gathering, creating labels to assign to deployments, creating groups based on one or two labels in a layered approach, and finally fixating the resulting schema and start mapping guidance documents (policies) toward the presented architecture.

As always, start with the requirements

From an infrastructure architect point of view, creating structure is one way of dealing with the onslaught in complexity that is prevalent within the wider organizational architecture. By creating a framework in which infrastructural services can be positioned, architects and other stakeholders (such as information security officers, process managers, service delivery owners, project and team leaders ...) can support the wide organization in its endeavor of becoming or remaining competitive.

Structure can be provided through various viewpoints. As such, while creating such framework, the initial intention is not to start drawing borders or creating a complex graph. Instead, look at attributes that one would assign to an infrastructural service, and treat those as labels. Create a nice portfolio of attributes which will help guide the development of such framework.

The following list gives some ideas in labels or attributes that one can use. But be creative, and use experienced people in devising the "true" list of attributes that fits the needs of your organization. Be sure to describe them properly and unambiguously - the list here is just an example, as are the descriptions.

- tenant identifies the organizational aggregation of business units which are sufficiently similar in areas such as policies (same policies in use), governance (decision bodies or approval structure), charging, etc. It could be a hierarchical aspect (such as organization) as well.

- location provides insight in the physical (if applicable) location of the service. This could be an actual building name, but can also be structured depending on the size of the environment. If it is structured, make sure to devise a structure up front. Consider things such as regions, countries, cities, data centers, etc. A special case location value could be the jurisdiction, if that is something that concerns the organization.

- service type tells you what kind of service an asset is. It can be a workstation, a server/host, server/guest, network device, virtual or physical appliance, sensor, tablet, etc.

- trust level provides information on how controlled and trusted the service is. Consider the differences between unmanaged (no patching, no users doing any maintenance), open (one or more admins, but no active controlled maintenance), controlled (basic maintenance and monitoring, but with still administrative access by others), managed (actively maintained, no privileged access without strict control), hardened (actively maintained, additional security measures taken) and kiosk (actively maintained, additional security measures taken and limited, well-known interfacing).

- compliance set identifies specific compliance-related attributes, such as the PCI-DSS compliancy level that a system has to adhere to.

- consumer group informs about the main consumer group, active on the service. This could be an identification of the relationship that consumer group has with the organization (anonymous, customer, provider, partner, employee, ...) or the actual name of the consumer group.

- architectural purpose gives insight in the purpose of the service in infrastructural terms. Is it a client system, a gateway, a mid-tier system, a processing system, a data management system, a batch server, a reporting system, etc.

- domain could be interpreted as to the company purpose of the system. Is it for commercial purposes (such as customer-facing software), corporate functions (company management), development, infrastructure/operations ...

- production status provides information about the production state of a service. Is it a production service, or a pre-production (final testing before going to production), staging (aggregation of multiple changes) or development environment?

Given the final set of labels, the next step is to aggregate results to create a high-level view of the environment.

Creating a layered structure

Chances are high that you'll end up with several attributes, and many of these will have multiple possible values. What we don't want is to end in an N-dimensional infrastructure architecture overview. Sure, it sounds sexy to do so, but you want to show the infrastructure architecture to several stakeholders in your organization. And projecting an N-dimensional structure on a 2-dimensional slide is not only challenging - you'll possibly create a projection which leaves out important details or make it hard to interpret.

Instead, we looked at a layered approach, with each layer handling one or two requirements. The top layer represents the requirement which the organization seems to see as the most defining attribute. It is the attribute where, if its value changes, most of its architecture changes (and thus the impact of a service relocation is the largest).

Suppose for instance that the domain attribute is seen as the most defining one: the organization has strict rules about placing corporate services and commercial services in separate environments, or the security officers want to see the commercial services, which are well exposed to many end users, be in a separate environment from corporate services. Or perhaps the company offers commercial services for multiple tenants, and as such wants several separate "commercial services" environments while having a single corporate service domain.

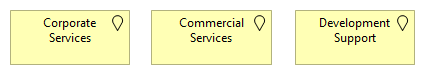

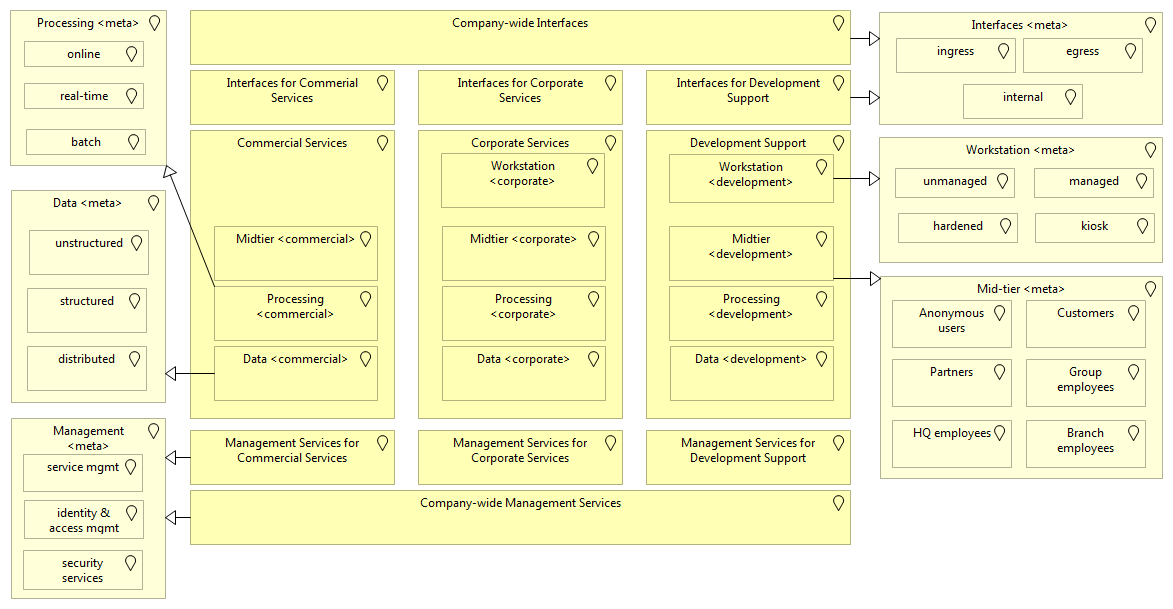

In this case, part of the infrastructure architecture overview on the top level could look like so (hypothetical example):

This also shows that, next to the corporate and commercial interests of the organization, a strong development support focus is prevalent as well. This of course depends on the type of organization or company and how significant in-house development is, but in this example it is seen as a major decisive factor for service positioning.

These top-level blocks (depicted as locations, for those of you using Archimate) are what we call "zones". These are not networks, but clearly bounded areas in which multiple services are positioned, and for which particular handling rules exist. These rules are generally written down in policies and standards - more about that later.

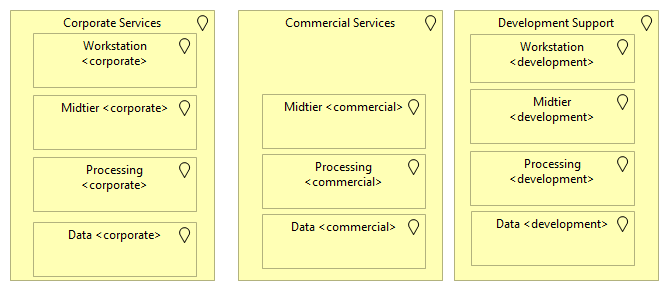

Inside each of these zones, a substructure is made available as well, based on another attribute. For instance, let's assume that this is the architectural purpose. This could be because the company has a requirement on segregating workstations and other client-oriented zones from the application hosting related ones. Security-wise, the company might have a principle where mid-tier services (API and presentation layer exposures) are separate from processing services, and where data is located in a separate zone to ensure specific data access or more optimal infrastructure services.

This zoning result could then be depicted as follows:

From this viewpoint, we can also deduce that this company provides separate workstation services: corporate workstation services (most likely managed workstations with focus on application disclosure, end user computing, etc.) and development workstations (most likely controlled workstations but with more open privileged access for the developer).

By making this separation explicit, the organization makes it clear that the development workstations will have a different position, and even a different access profile toward other services within the company.

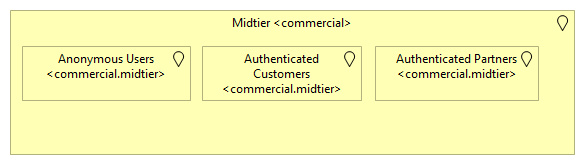

We're not done yet. For instance, on the mid-tier level, we could look at the consumer group of the services:

This separation can be established due to security reasons (isolating services that are exposed to anonymous users from customer services or even partner services), but one can also envision this to be from a management point of view (availability requirements can differ, capacity management is more uncertain for anonymous-facing services than authenticated, etc.)

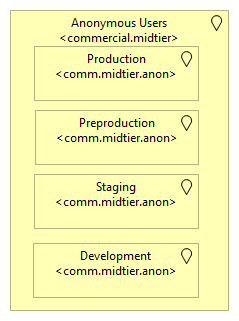

Going one layer down, we use a production status attribute as the defining requirement:

At this point, our company decided that the defined layers are sufficiently established and make for a good overview. We used different defining properties than the ones displayed above (again, find a good balance that fits the company or organization that you're focusing on), but found that the ones we used were mostly involved in existing policies and principles, while the other ones are not that decisive for infrastructure architectural purposes.

For instance, the tenant might not be selected as a deciding attribute, because there will be larger tenants and smaller tenants (which could make the resulting zone set very convoluted) or because some commercial services are offered toward multiple tenants and the organizations' strategy would be to move toward multi-tenant services rather than multiple deployments.

Now, in the zoning structure there is still another layer, which from an

infrastructure architecture point is less about rules and guidelines and more

about manageability from an organizational point of view. For instance, in the

above example, a SAP deployment for HR purposes (which is obviously a corporate

service) might have its Enterprise Portal service in the Corporate Services >

Mid-tier > Group Employees > Production zone. However, another service such as

an on-premise SharePoint deployment for group collaboration might be in Corporate

Services > Mid-tier > Group Employees > Production zone as well. Yet both

services are supported through different teams.

This "final" layer thus enables grouping of services based on the supporting team (again, this is an example), which is organizationally aligned with the business units of the company, and potentially further isolation of services based on other attributes which are not defining for all services. For instance, the company might have a policy that services with a certain business impact assessment score must be in isolated segments with no other deployments within the same segment.

What about management services

Now, the above picture is missing some of the (in my opinion) most important services: infrastructure support and management services. These services do not shine in functional offerings (which many non-IT people generally look at) but are needed for non-functional requirements: manageability, cost control, security (if security can be defined as a non-functional - let's not discuss that right now).

Let's first consider interfaces - gateways and other services which are positioned between zones or the "outside world". In the past, we would speak of a demilitarized zone (DMZ). In more recent publications, one can find this as an interface zone, or a set of Zone Interface Points (ZIPs) for accessing and interacting with the services within a zone.

In many cases, several of these interface points and gateways are used in the organization to support a number of non-functional requirements. They can be used for intelligent load balancing, providing virtual patching capabilities, validating content against malware before passing it on to the actual services, etc.

Depending on the top level zone, different gateways might be needed (i.e. different requirements). Interfaces for commercial services will have a strong focus on security and manageability. Those for the corporate services might be more integration-oriented, and have different data leakage requirements than those for commercial services.

Also, inside such an interface zone, one can imagine a substructure to take place as well: egress interfaces (for communication that is exiting the zone), ingress interfaces (for communication that is entering the zone) and internal interfaces (used for routing between the subzones within the zone).

Yet, there will also be requirements which are company-wide. Hence, one could envision a structure where there is a company-wide interface zone (with mandatory requirements regardless of the zone that they support) as well as a zone-specific interface zone (with the mandatory requirements specific to that zone).

Before I show a picture of this, let's consider management services. Unlike interfaces, these services are more oriented toward the operational management of the infrastructure. Software deployment, configuration management, identity & access management services, etc. Are services one can put under management services.

And like with interfaces, one can envision the need for both company-wide management services, as well as zone-specific management services.

This information brings us to a final picture, one that assists the organization in providing a more manageable view on its deployment landscape. It does not show the 3rd layer (i.e. production versus non-production deployments) and only displays the second layer through specialization information, which I've quickly made a few examples for (you don't want to make such decisions in a few hours, like I did for this post).

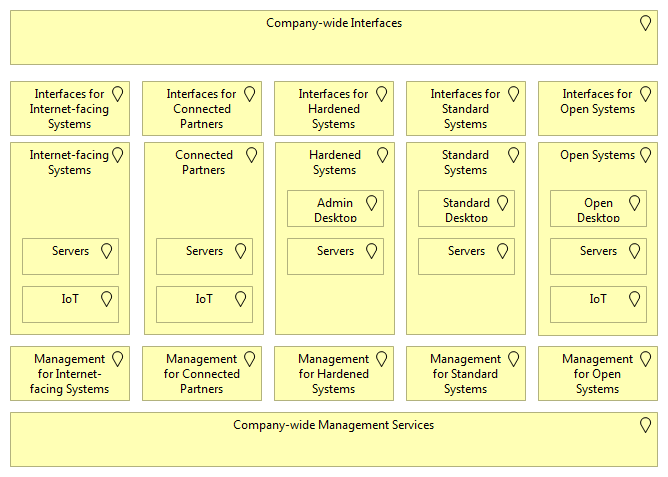

If the organization took an alternative approach for structuring (different requirements and grouping) the resulting diagram could look quite different:

Flows, flows and more flows

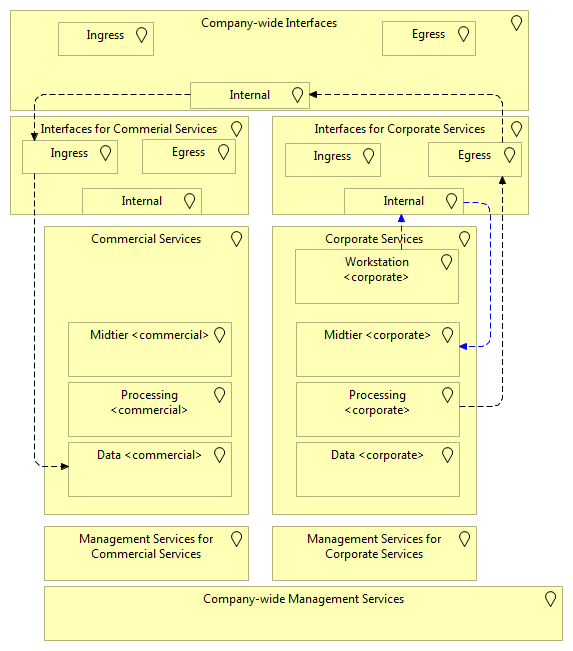

With the high-level picture ready, it is not a bad idea to look at how flows are handled in such an architecture. As the interface layer is available on both company-wide level as well as the next, flows will cross multiple zones.

Consider the case of a corporate workstation connecting to a reporting server

(like a Cognos or PowerBI or whatever fancy tool is used), and this reporting

server is pulling data from a database system. Now, this database system is

positioned in the Commercial zone, while the reporting server is in the

Corporate zone. The flows could then look like so:

Note for the Archimate people: I'm sorry that I'm abusing the flow relation here. I didn't want to create abstract services in the locations and then use the "serves" or "used by" relation and then explaining readers that the arrows are then inverse from what they imagine.

In this picture, the corporate workstation does not connect to the reporting server directly. It goes through the internal interface layer for the corporate zone. This internal interface layer can offer services such as reverse proxies or intelligent load balancers. The idea here is that, if the organization wants, it can introduce additional controls or supporting services in this internal interface layer without impacting the system deployments themselves much.

But the true flow challenge is in the next one, where a processing system connects to a data layer. Here, the processing server will first connect to the egress interface for corporate, then through the company-wide internal interface, toward the ingress interface of the commercial and then to the data layer.

Now, why three different interfaces, and what would be inside it?

On the corporate level, the egress interface could be focusing on privacy controls or data leakage controls. On the company-wide internal interface more functional routing capabilities could be provided, while on the commercial level the ingress could be a database activity monitoring (DAM) system such as a database firewall to provide enhanced auditing and access controls.

Does that mean that all flows need to have at least three gateways? No, this is a functional picture. If the organization agrees, then one or more of these interface levels can have a simple pass-through setup. It is well possible that database connections only connect directly to a DAM service and that such flows are allowed to immediately go through other interfaces.

The importance thus is not to make flows more difficult to provide, but to provide several areas where the organization can introduce controls.

Making policies and standards more visible

One of the effects of having a better structure of the company-wide deployments (i.e. a good zoning solution) is that one can start making policies more clear, and potentially even simple to implement with supporting tools (such as software defined network solutions).

For instance, a company might want to protect its production data and establish that it cannot be used for non-production use, but that there are no restrictions for the other data environments. Another rule could be that web-based access toward the mid-tier is only allowed through an interface.

These are simple statements which, if a company has a good IP plan, are easy to implement - one doesn't need zoning, although it helps. But it goes further than access controls.

For instance, the company might require corporate workstations to be under

heavy data leakage prevention and protection measures, while developer

workstations are more open (but don't have any production data access). This

not only reveals an access control, but also implies particular minimal

requirements (for the Corporate > Workstation zone) and services (for the

Corporate interfaces).

This zoning structure does not necessarily make any statements about the location (assuming it isn't picked as one of the requirements in the beginning). One can easily extend this to include cloud-based services or services offered by third parties.

Finally, it also supports making policies and standards more realistic. I often see policies that make bold statements such as "all software deployments must be done through the company software distribution tool", but the policies don't consider development environments (production status) or unmanaged, open or controlled deployments (trust level). When challenged, the policy owner might shrug away the comment with "it's obvious that this policy does not apply to our sandbox environment" or so.

With a proper zoning structure, policies can establish the rules for the right set of zones, and actually pin-point which zones are affected by a statement. This is also important if a company has many, many policies. With a good zoning structure, the policies can be assigned with meta-data so that affected roles (such as project leaders, architects, solution engineers, etc.) can easily get an overview of the policies that influence a given zone.

For instance, if I want to position a new management service, I am less concerned about workstation-specific policies. And if the management service is specific for the development environment (such as a new version control system) many corporate or commercially oriented policies don't apply either.

Conclusion

The above approach for structuring an organization is documented here in a high-level manner. It takes many assumptions or hypothetical decisions which are to be tailored toward the company itself. In my company, a different zoning structure is selected, taking into account that it is a financial service provider with entities in multiple countries, handling several thousand of systems and with an ongoing effort to include cloud providers within its infrastructure architecture.

Yet the approach itself is followed in an equal fashion. We looked at requirements, created a layered structure, and finished the zoning schema. Once the schema was established, the requirements for all the zones were written out further, and a mapping of existing deployments (as-is) toward the new zoning picture is on-going. For those thinking that it is just slideware right now - it isn't. Some of the structures that come out of the zoning exercise are already prevalent in the organization, and new environments (due to mergers and acquisitions) are directed to this new situation.

Still, we know we have a large exercise ahead before it is finished, but I believe that it will benefit us greatly, not only from a security point of view, but also clarity and manageability of the environment.